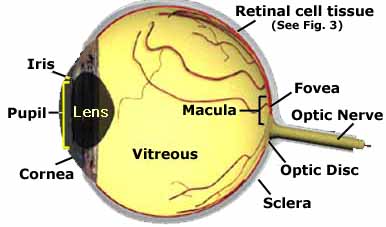

So your sight is slowly diminishing, and your ophthalmologist told you that nothing could be done. They said that the cells in the very center of your retina (the macula) are degenerating, and gradual loss of clear eyesight is to be expected. Still, they want to see you at least once a year unless you notice a sudden change in your vision.

Over the ensuing months, you dutifully check the Amsler grid taped to your mirror, one eye at a time as recommended, and you haven’t seen any reason to call the clinic. You do, however, notice that, sure enough, your vision is getting dimmer and less clear over time, just as you were told.

The year passes, and you have grown accustomed to making do with better lighting and magnification, even though you’re struggling more and more with seeing at a distance. You know about low vision rehabilitation opportunities, but your vision is not severe enough for qualification, and you feel that you don’t yet need that kind of intervention. You ask yourself, “Do I really need to make that appointment? I’m seeing a little more blurriness and glare, but nothing the doctor can fix. So maybe I’ll save the time and trouble of getting to the clinic and sitting for hours in that waiting room”.

Here’s something to consider before making that decision:

Your progressive vision loss could be blamed on more than your macula. Your diminishing eyesight might signify one or more conditions that can be treated, even if your macula cannot. If you have another condition affecting your vision, that’s called a co-morbidity. You may not know that your doctor examines you for co-morbidities, an especially important protocol for aging eyes. If any are found, they may or may not tell you right away, but they will make a note in your record for follow-up and possible treatment.

The National Eye Institute (NEI) defines common causes of vision loss that can occur simultaneously with retinal disease in senior adults. The number of possibilities might surprise you, but the good news is that many of them are treatable if identified in time. In addition to tracking the progression of your macular condition, a regular dilated exam for co-morbidities is an important reason for that annual visit with your doctor. You might find that you have an alternative explanation for your worsening vision that can be corrected. As described by the NEI, here are the five most common treatable vision problems in older adults that cannot be blamed on the macula:

Cataract

A cataract is a cloudy area in the lens of your eye. Cataracts are very common as you get older. In fact, more than half of all Americans age 80 or older either have cataracts or have had surgery to get rid of cataracts. More information: https://www.nei.nih.gov/learn-about-eye-health/eye-conditions-and-diseases/cataracts

Dry Eye

Dry eye happens when your eyes don’t make enough tears to stay wet, or when your tears don’t work correctly. This can make your eyes feel uncomfortable, and in some cases it can also cause vision problems. More information: https://www.nei.nih.gov/learn-about-eye-health/eye-conditions-and-diseases/dry-eye

Floaters

Floaters are small dark shapes that float across your vision. They can look like spots, threads, squiggly lines, or even little cobwebs. More information: https://www.nei.nih.gov/learn-about-eye-health/eye-conditions-and-diseases/floaters

Glaucoma

Glaucoma is a group of eye diseases that can cause vision loss and blindness by damaging . . . the optic nerve. More information: https://www.nei.nih.gov/learn-about-eye-health/eye-conditions-and-diseases/glaucoma

Refractive Errors (presbyopia, astigmatism, nearsightedness, farsightedness)

Refractive errors happen when the shape of your eye keeps light from focusing correctly on your retina. Sometimes, all you need is better eyeglasses. More information: https://www.nei.nih.gov/learn-about-eye-health/eye-conditions-and-diseases/refractive-errors

Take-away: Your annual exam may take a day out of your year, but it could add years to your vision!

by Dan Roberts, Editor-in-Chief

Living Well With Low Vision